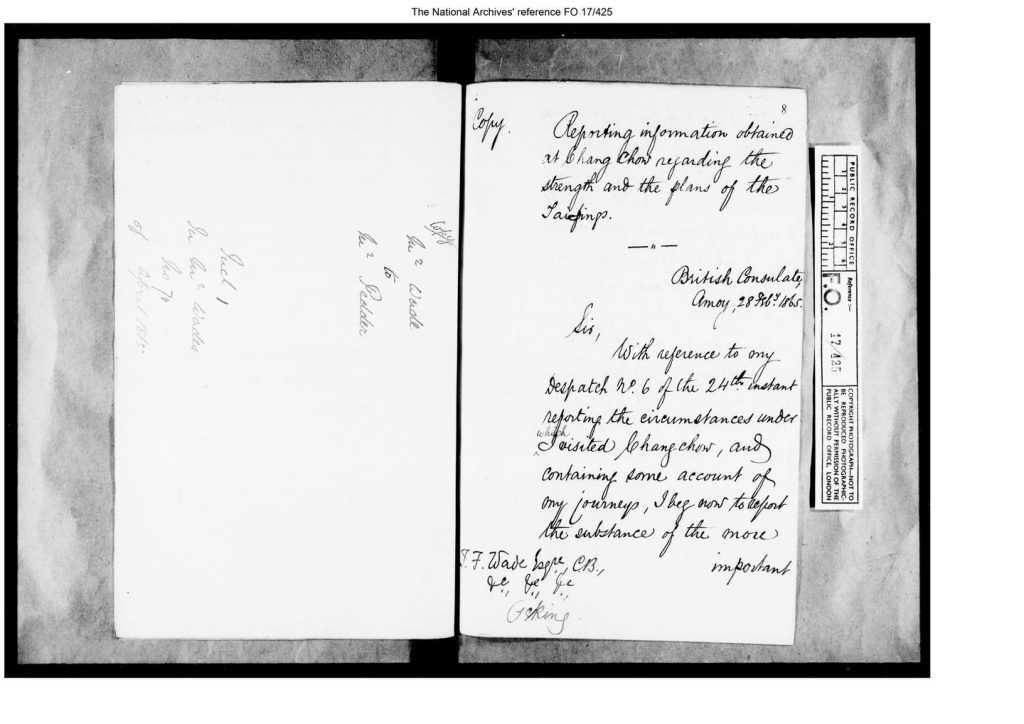

Reporting information obtained at Chang Chow regarding the strength and the plans of the Taipings.(1865年2月柏威林漳州访李世贤见闻)

标题:《Reporting information obtained at Chang Chow regarding the strength and the plans of the Taipings.》(1865年2月柏威林漳州访李世贤见闻)

作者:William Henry Pedder(柏威林)

原载:United Kingdom National Archies, Records created or inherited by the Foreign Office, FO-17/425

转录:chat gpt

译者:chat gpt

译文校正:苏三

原件

英文抄录

Copy

Reporting information obtained at Chang Chow regarding the strength and the plans of the Taipings.

British Consulate,

Amoy, 28 Feb.1865.

Sir,

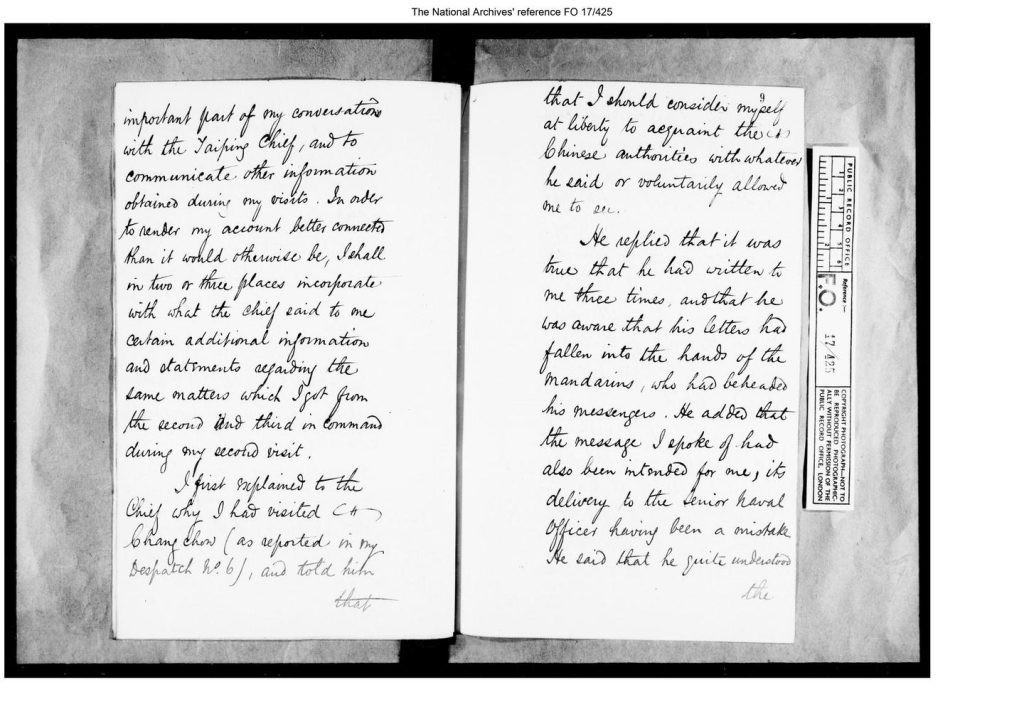

With reference to my Despatch No. 6 of the 24th instant reporting the circumstances under which I visited Changchow, and containing some account of my journey, I beg now to report the substance of the more important part of my conversation with the Taiping Chief, and to communicate other information obtained during my visits. In order to render my account better connected than it would otherwise be, I shall in two or three places incorporate with what the Chief said to me certain additional information and statements regarding the same matters which I got from the second and third in command during my second visit.

I first explained to the Chief why I had visited Changchow (as reported in my Despatch No. 6), and told him that I should consider myself at liberty to acquaint the Chinese authorities with whatever he said or voluntarily allowed me to see.

He replied that it was true that he had written to me three times, and that he was aware that his letters had fallen into the hands of the Mandarins, who had beheaded his messengers. He added that the message I spoke of had also been intended for me, its delivery to the senior naval officer having been a mistake. He said that he quite understood the propriety of my communicating everything to the mandarins with whom I was on terms of official friendliness; that he had not the least objection to my doing so; and that on the following day (it was then dark) he would take me round the walls and all over the city, so that I might be able to take back an interesting report.

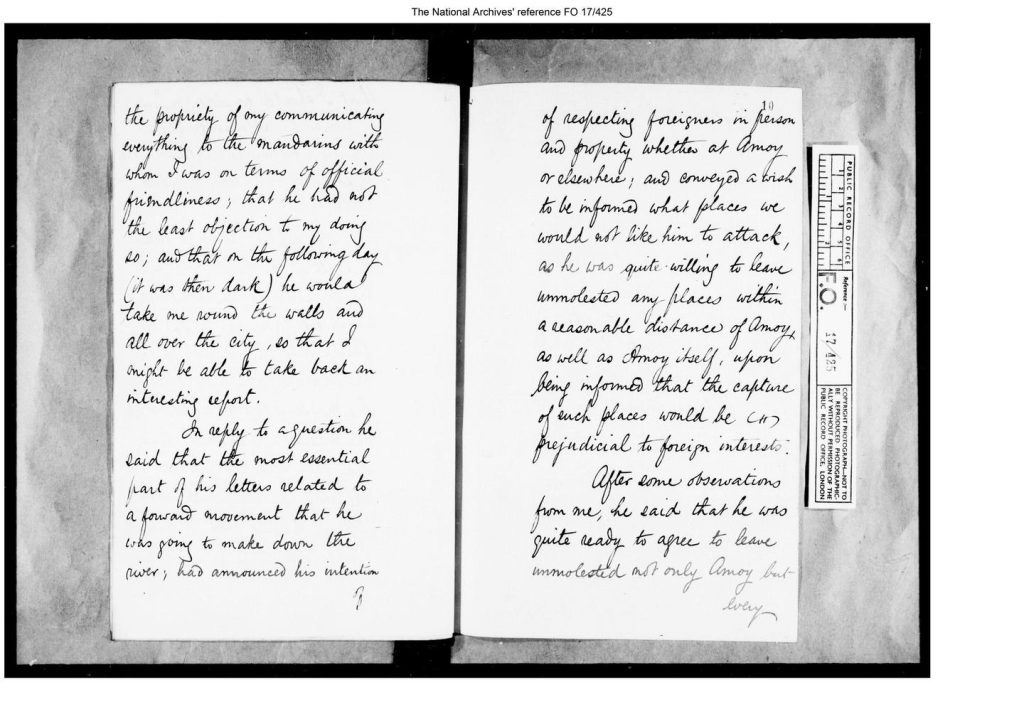

In reply to a question he said that the most essential part of his letters related to a forward movement that he was going to make down the river; had announced his intention of respecting foreigners in person and property, whether at Amoy or elsewhere; and conveyed a wish to be informed what places we would not like him to attack, as he was quite willing to leave unmolested any places within a reasonable distance of Amoy as well as Amoy itself, upon being informed that the capture of such places would be prejudicial to foreign interests.

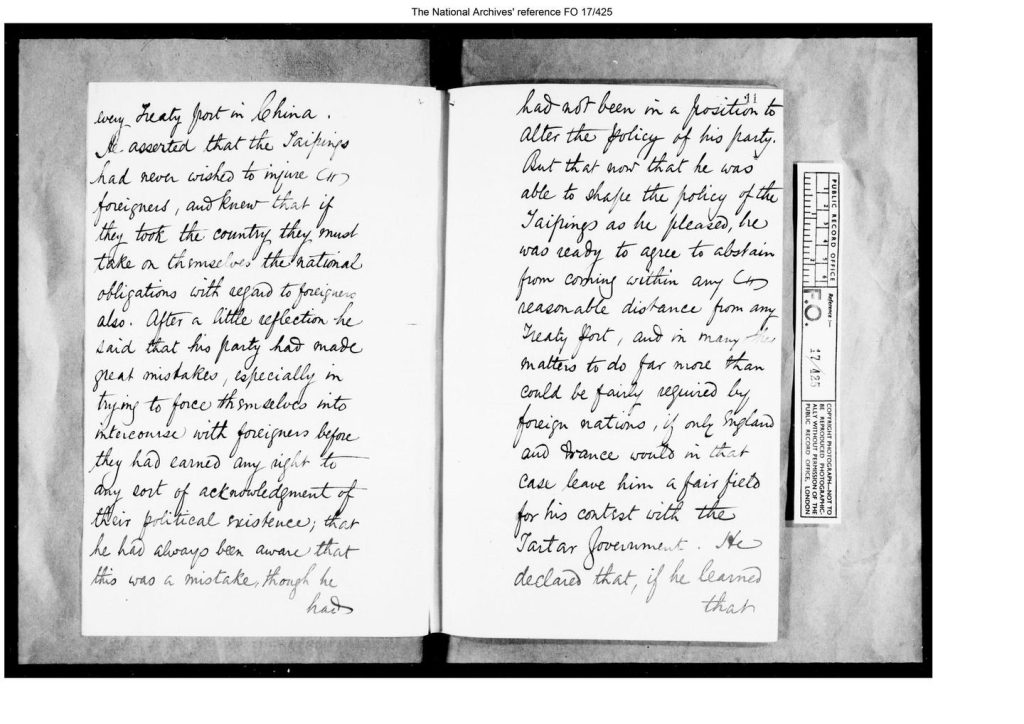

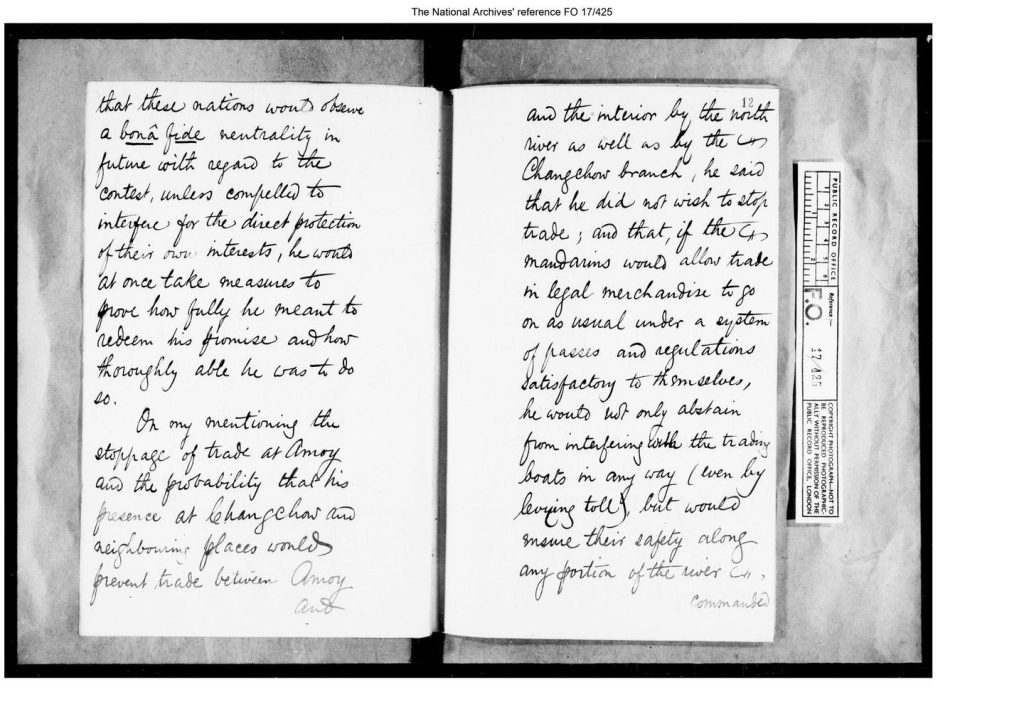

After some observations from me, he said that he was quite ready to agree to leave unmolested not only Amoy but every treaty port in China. He asserted that the Taipings had never wished to injure foreigners, and knew that if they took the country they must take on themselves the national obligations with regard to foreigners also. After a little reflection, he said that his party had made great mistakes, especially in trying to force themselves into intercourse with foreigners before they had earned any right to any sort of acknowledgment of their political existence; that he had always been aware that this was a mistake, though he had not been in a position to alter the policy of his party. But that now that he was able to shape the policy of the Taipings as he pleased, he was ready to agree to abstain from coming within any reasonable distance from any treaty port, and in many matters to do far more than could be fairly required by foreign nations, if only England and France would in that case leave him a fair field for his contest with the Tartar Government. He declared that, if he learned that these nations would observe a bona fide neutrality in future with regard to the contest, unless compelled to interfere for the direct protection of their own interests, he would at once take measures to prove how fully he meant to redeem his promises and how thoroughly able he was to do so.

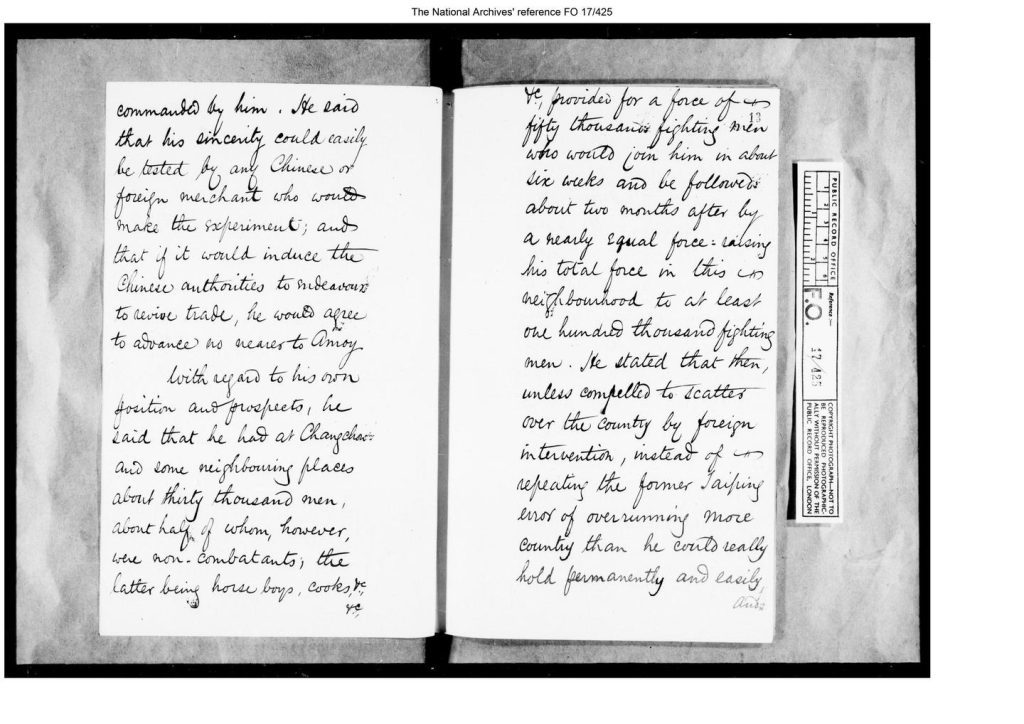

On my mentioning the stoppage of trade at Amoy and the probability that his presence at Changchow and neighboring places would prevent trade between Amoy and the interior by the north river as well as by the Changchow branch, he said that he did not wish to stop trade; and that, if the mandarins would allow trade in legal merchandise to go on as usual under a system of places and regulations satisfactory to themselves, he would not only abstain from interfering with the trading boats in any way (even by levying toll), but would ensure their safety along any portion of the river commanded by him. He said that his sincerity could easily be tested by any Chinese or foreign merchant who would make the experiment; and that if it would induce the Chinese authorities to endeavor to revive trade, he would agree to advance no nearer to Amoy.

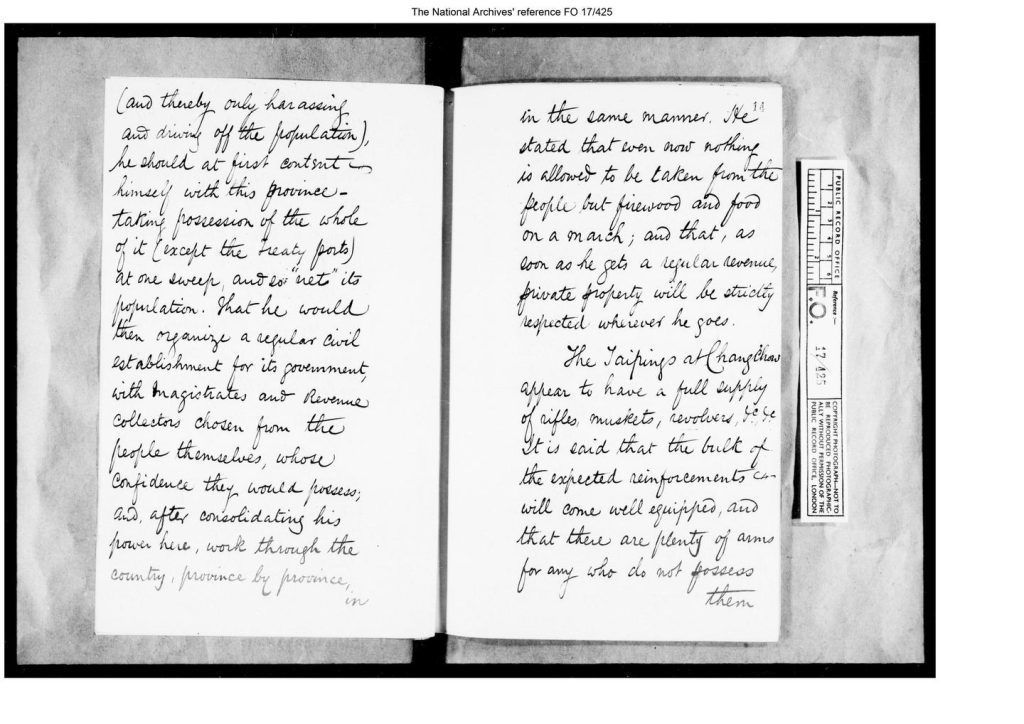

With regard to his own position and prospects, he said that he had at Changchow and some neighboring places about thirty thousand men, about half of whom, however, were non-combatants, the latter being horse boys, cooks, &c. He provided for a force of fifty thousand fighting men who would join him in about six weeks and be followed about two months after by a nearly equal force; raising his total force in this neighborhood to at least one hundred thousand fighting men. He stated that then, unless compelled to scatter over the country by foreign intervention, instead of repeating the former Taiping error of overrunning more country than he could really hold permanently and easily (and thereby only harassing and driving off the population), he should at first content himself with this province——taking possession of the whole of it (except the treaty ports) at one sweep, and so “net” its population. That he would then organize a regular civil establishment for its government with magistrates and revenue collectors chosen from the people themselves, whose confidence they would possess; and, after consolidating his power here, work through the country, province by province, in the same manner. He stated that even now nothing is allowed to be taken from the people but firewood and food on a march; and that, as soon as he gets a regular revenue, private property will be strictly respected wherever he goes.

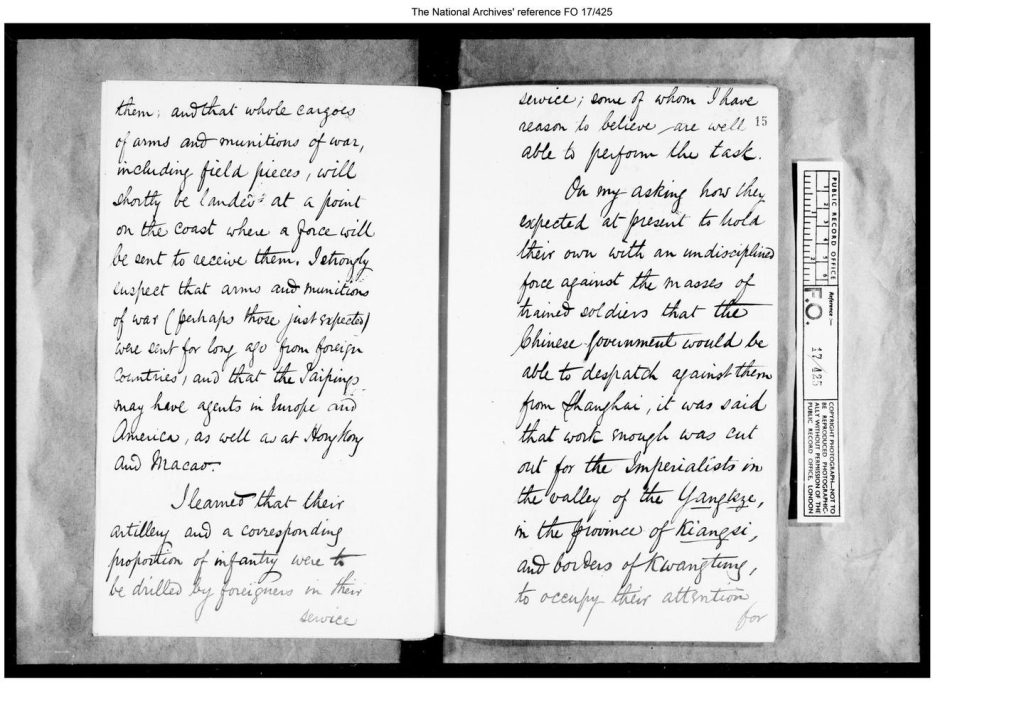

The Taipings at Changchow appear to have a full supply of rifles, muskets, revolvers, &c. It is said that the bulk of the expected reinforcements will come well equipped, and that there are plenty of arms for any who do not possess them; and that whole cargoes of arms and munitions of war, including field pieces, will shortly be landed at a point on the coast where a force will be sent to receive them. I strongly suspect that arms and munitions of war (perhaps those just rejected) were sent for long ago from foreign countries, and that the Taipings may have agents in Europe and America, as well as at Hong Kong and Macao.

I learned that their artillery and a corresponding proportion of infantry were to be drilled by foreigners in their service; some of whom I have reason to believe are well able to perform the task.

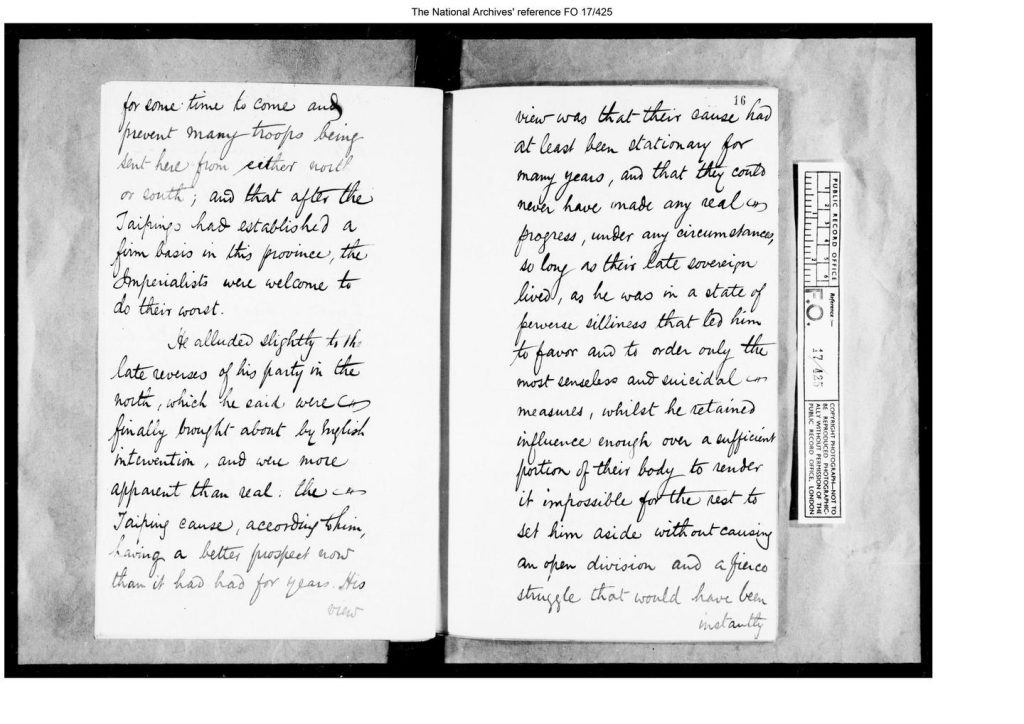

On my asking how they expected at present to hold their own with an undisciplined force against the masses of trained soldiers that the Chinese government would be able to despatch against them from Shanghai, it was said that work enough was cut out for the Imperialists in the valley of the Yangtze, in the provinces of Kiangsei and borders of Kwangtung, to occupy their attention for some time to come and prevent many troops being sent here from either north or south; and that after the Taipings had established a firm basis in this province, the Imperialists were welcome to do their worst.

He alluded slightly to the late reverses of his party in the north, which he said were finally brought about by English intervention and were more apparent than real; the Taiping cause, according to him, having a better prospect now than it had had for years. His view was that their cause has at least been stationary for many years, and that they could never have made any real progress, under any circumstances, so long as their late sovereign lived, as he was in a state of perverse silliness that led him to favor and to order only the most senseless and suicidal measures, whilst he retained influence enough over a sufficient portion of their body to render it impossible for the rest to set him aside without causing an open division and a fierce struggle that would have been instantly destructive to the cause. Under these circumstances, the result of the late operations in the north was to free the movement from a fatal influence under which the negative evils of indecision and inactivity were less to be feared than active measures which were certain to be actively pernicious.

The Chief, whose name is written in the margin, is a tall, handsome man about thirty-five years of age, with a somewhat pensive expression and a cast of countenance that I have never before seen amongst Chinese. He is said to be a half-brother of the Chung Wang (by the same father), and says that he belongs to a village near Changchow——though brought up almost from infancy in a different part of the Empire. His followers, who are from a dozen different provinces, say that he can speak all their various dialects fluently, that he knows every individual by name, and never fails to speak to each in his own tongue. His bearing is most simple and unassuming; his manner is that of an English gentleman, and not that with regard to pillaging, for they roam about in small parties in the surrounding villages without causing any alarm. Indeed, the country people keep the city well supplied with provisions, going in without fear, and, they say, getting paid for everything.

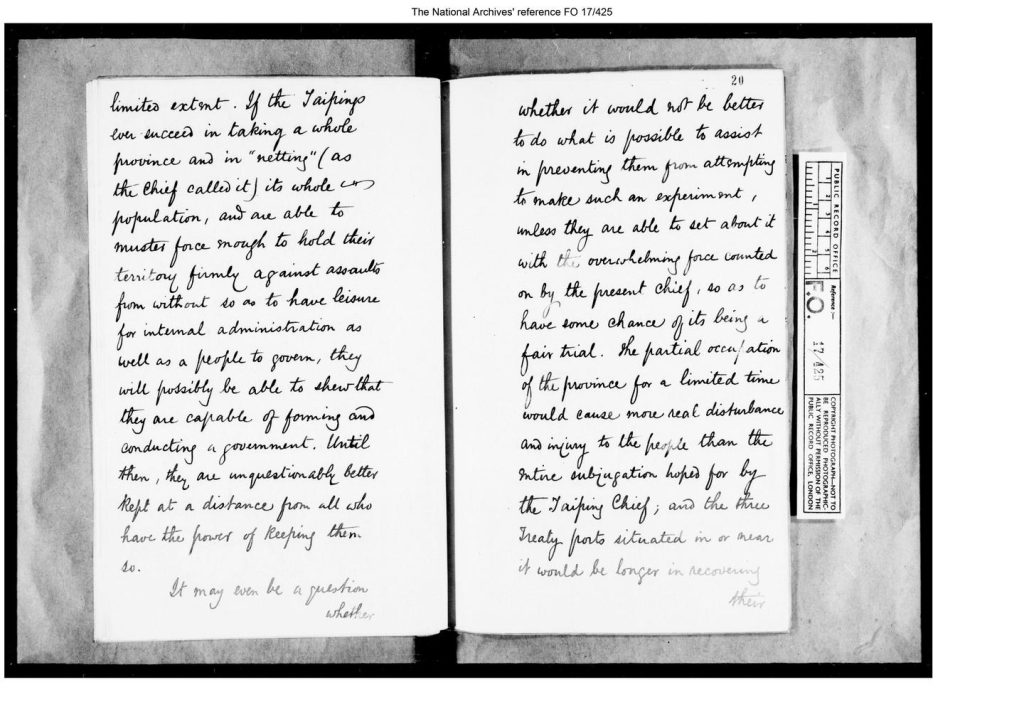

But it would be impossible to detail all I saw on my visits. The result of all was to confirm me in the belief that their presence in any isolated places is an unmitigated evil of the greatest magnitude, and that they should never be allowed to capture any place where foreigners reside, and where foreign nations have any semblance of a right to interfere for its protection. Mandarin rule is bad enough, but society can and does exist under it. I do not see how it could do so in any place under the rule of mere fighting men engaged in constant battling for bare existence. The dispersion of the population with its attendant losses and sufferings is the least evil that can happen, and is one which would always occur in any town or portion of country of limited extent. If the Taipings ever succeed in taking a whole province and in “”netting” (as the Chief called it) its whole population, and are able to muster force enough to hold their territory firmly against assaults from without so as to have leisure for internal administration as well as a people to govern, they will possibly be able to show that they are capable of forming and conducting a government. Until then, they are unquestionably better kept at a distance from all who have the power of keeping them so.

It may even be a question whether it would not be better to do what is possible to assist in preventing them from attempting to make such an experiment, unless they are able to set about it with the overwhelming force counted on by the present chief, so as to have some chance of its being a fair trial. The partial occupation of the province for a limited time would cause more real disturbance and injury to the people than the entire subjugation hoped for by the Taiping Chief; and the three treaty ports situated in or near it would be longer in recovering their commercial prosperity on the return of uninterrupted trade.

Yours Respectfully,

(Signed) W.H.Pedder

中文翻译

关于在漳州获得的有关太平军实力及计划的信息报告

英国领事馆,

厦门,1865年2月28日

尊敬的先生:

我在本月24日所发的第6号报告记录了我访问漳州的情况,并简要描述了我的旅程,现在我请求报告与太平军首领会谈的主要内容,并传达我访问期间获得的其他信息。为了使我的报告更加连贯,我会在本文的两三处将首领对我说的话与我第二次访问时从第二号、第三号指挥官处获得的关于相同问题的额外信息和陈述结合起来。

首先,我向首领解释了我为什么要访问漳州(如我在第6号报告中所述),并告诉他,我可以自由地将他所说的话或他自愿让我看到的任何内容告知中国当局。

他回答说,他确实给我写过三次信,他也知道他的信件落入了满人手中,送信的使者被斩首。他补充说,我提到的消息也确实是给我的,送到海军高级军官手中的那封信是一场误会。他表示,他完全理解我在与满人保持官方友好关系的前提下,有责任将一切内容告知他们,他对此没有丝毫异议。他说第二天(当时天色已暗)会带我巡视城墙和整个城市,让我可以带回一份有趣的报告。

在回答我的一个问题时,他说,他的信件中最重要的部分涉及他准备沿河发起的进攻行动,他在信中宣告了尊重外国人及其财产的意图,无论是在厦门还是其他地方,并在信中表示他希望了解我们不希望他攻击哪些地区。他愿意将军队置于这些地区合理距离之外,只要他被告知占领这些地区会损害外国利益。

在我提出了一些意见后,他说他完全愿意不进攻厦门以及中国的所有条约港口。他声称太平军从未想过伤害外国人,并且他们知道,如果他们占领了这个国家,他们必须承担与外国有关的国家义务。在稍作思考后,他表示,他的党派犯了很多错误,尤其是在没有获得任何承认其政治存在的权利之前,试图强行与外国人交往;他一直知道这是个错误,虽然当时他没有能力改变他的党派的政策。但是现在他能够按自己的意愿制定太平军的政策。他愿意同意不接近任何条约港口,并在许多问题上对外国作出远超合理限度的让步,只要英法两国能够让他与满清政府展开公平的较量。他宣称,如果他得知这些国家未来能够在这场斗争中保持真正的中立,除非是为了直接保护自己的利益而被迫干预,他将立即采取措施证明他完全兑现承诺的决心和能力。

我提到厦门贸易出现停滞,他在漳州及其周边地区的存在可能阻碍厦门与内地通过北河以及漳州支流的贸易,他说他并不希望停止贸易;如果满人允许合法商品贸易按他们自己满意的方式和规则继续进行,他不仅不会以任何方式干扰贸易船只(甚至不征收通行税),还会确保他控制的河流段上所有船只的安全。他说,中国或外国商人可以通过实际行动来检验他的真诚,如果这能促使中国当局努力恢复贸易,他将同意不进一步接近厦门。

关于他自己的地位和前景,他说在漳州及其附近地区有大约三万人,其中大约一半是非战斗人员,这些人是马童、厨师等。他为约五万名战斗人员的到来做了准备,他们将在大约六周内加入,大约两个月后,再有一支几乎同样规模的部队跟进;这样的话,他在这个地区的总兵力将达到至少十万名战斗人员。他表示,除非外国干涉迫使他们分散在各地,他将不再重蹈过去太平军的覆辙——以往太平军占领的领土超出他们能长久控制的范围,以至于他们只能骚扰并驱赶人口。他将首先满足于占领这个省的全部——除了条约港口,并“网罗”该省全部人口。然后,他会为其政府组织一个正规文职机构,选出本地行政长官和税务官来管理,因为他们会得到人民的信任;在巩固了此地的权力后,他将以同样的方式逐省推进。他表示,即使是现在,他的军队也只是在行军中从百姓那里获取柴火和食物;一旦他有了正规财政收入,私有财产在他所到之处将得到严格保护。

漳州的太平军似乎有充足的来复枪、滑膛枪、左轮手枪等。据信,大部分预期的增援部队将装备精良,任何没有武器的人也有充足的武器供应;整批的武器和战争物资,包括野战火炮,将很快在海岸的一处地点卸下,有一支部队将被派去接收。我强烈怀疑这些武器和战争物资(也许是那些刚刚被拒绝的)早在很久以前就已从外国订购,并且太平军可能在欧洲、美国以及香港和澳门都有代理人。

我了解到他们的炮兵和相应比例的步兵将由外国人训练,我有理由相信其中一些人完全有能力胜任这一任务。

当我询问他们如何期待以一支未经训练的部队抵抗中国政府从上海派来的大量训练有素的士兵时,他们表示,在长江流域,特别是江西省和广东边境,已经有足够多的工作要让清军忙个不停,使他们无法从北方或南方派遣大量部队到这里;在太平军在这一省份建立牢固的根据地之后,欢迎清军尽其所能。

首领稍微提了一下他的党派最近在北方遭遇的挫折,他说这些挫折最终是由英国干预造成的,并且实际情况没有看起来那么严重;据他说,太平军的前景比近年来任何时候都要好。他认为,他们的事业多年来至少是停滞不前的,只要他们那位已故的君主[1]还在,他们永远无法在任何情况下取得任何真正的进展,因为此人极其愚蠢,只喜欢并下令采取最无意义、最自杀性的措施。与此同时,他在党派内保有足够的影响力,以至于其余的人无法将他置之不理,否则会引发公开分裂和激烈的斗争,这将立即摧毁这个事业。在这种情况下,北伐最近的战役结果让这场运动摆脱了一个致命的影响。在此影响下,与其说担心优柔寡断和不作为带来的消极后果,不如说担心积极的措施会带来破坏力更大的有害后果。

首领的名字写在页边[2],他是一位大约三十五岁的高大英俊男子,表情有些忧郁,拥有一种我从未在其他中国人身上见过的面相。据说他是忠王的同父异母兄弟。他说他来自漳州附近的一个村庄——尽管几乎从幼年起,他便在帝国的另一个地区长大。他的追随者来自十几个不同的省份,他们说他能流利地讲所有这些地区的方言,他知道每个人的名字,并且从未忘记用他们的母语与他们交谈。他的举止非常简单谦逊,风度像一位英国绅士,而不是土匪。他的部队四散在周围的村庄里游荡,却没有引起任何恐慌。事实上,当地百姓毫无恐惧地向城市供应粮食,据说他们所提供的一切都得到了报酬。

但我无法详细描述在访问中看到的一切景象。所有这些都让我更加确信,太平军的存在对任何孤立地区来说都是一个极其严重的灾难,他们不应被允许占领任何有外国人居住的地方,也不应占领外国国家有权干预保护的地方。满人的统治虽然糟糕,但社会还能在其统治下存在。当任何地区由一群为生存而不断作战的武装人员统治时,我看不出当地的社会要如何存续。人口的分散及随之而来的损失和痛苦是最小的灾难,这种情况在任何有限范围内的城市或乡村都会发生。如果太平军有朝一日能够占领整个省份,并像首领所说的那样“网罗”其全部人口、集结足够力量,坚守领土,抵御外部攻击,进而有时间进行内部管理,并拥有可以统治的人民,那么他们或许能证明他们有能力组建并管理一个政府。在此之前,毫无疑问,最好让他们远离所有能将他们拒之门外的地方。

甚至可以讨论是否应该尽一切可能阻止他们如此尝试,除非他们能像现任首领所期望的那样,以压倒性的力量展开行动,以确保这一尝试有成功的可能。在一定时间内,比起太平军首领所希望的整个省份的完全征服,省份的部分占领将给人民带来更多的真正动荡和损失;该省的三个条约港口在恢复不间断的贸易后,也会需要更长的时间,才能恢复其商业繁荣。

此致

敬礼,

(签名)W.H.Peddar[3]

参考

- 指洪秀全。

- 原件页边上写着李世贤的拼音。

- 即William Henry Pedder(柏威林)。